SA008.

Empowered Structures

Empowered Structures

This essay originally appeared in Design Advocates, Journal #1.

In New York City in the winter of 2020/21 the streets and sidewalks have acquired characteristics of a new and unknown terrain. Like the landscape of a dream they are somehow the same and yet fundamentally different; less a landmark seen through the fog than a friend recast by parenthood. It will take some time to get used to this new presence, and yet we are simultaneously inventing it. These streets are no longer just our familiar zone of movement and infrastructure. Those systems, which privileged regularity and repetition, have given way to something that operates according to different rules. What was only a parking space is now also a dining space; what was previously exterior has become tentatively interior; what recently operated beyond the proclivities of real estate is now very much within it.

As the city’s understanding of its own urbanity mutates, the street has become its most visible laboratory. The reality of our offices and homes have been subject to an equally forcible reassessment, but it has occurred somewhat out of view. The street is a pervasive feature of the city, a network that joins us into blocks and larger more abstract units like neighborhoods and boroughs. Its everywhere-ness along with its exterior-ness – as well as the relative lack of private control – makes it a useful and practical public health tool and returns urbanism to an epidemiological role it has played many times before. But for all the talk of prototypes and policy, this time the urbanism is relatively non-infrastructural. The most effective strategies have played out at the scale of the single storefront, the single business owner, and the uncoordinated efforts of many small contractors and unlicensed builders. The speed and informality of the changes are primary features. This version of pandemic urbanism relies on an urgent bargain where fallow real estate has been put back into economic production in exchange for a new set of behaviors. We do on the street what we once did on the interior while the interior has become a place of movement that we pass through to make our transactions rather than a space where we dwell.

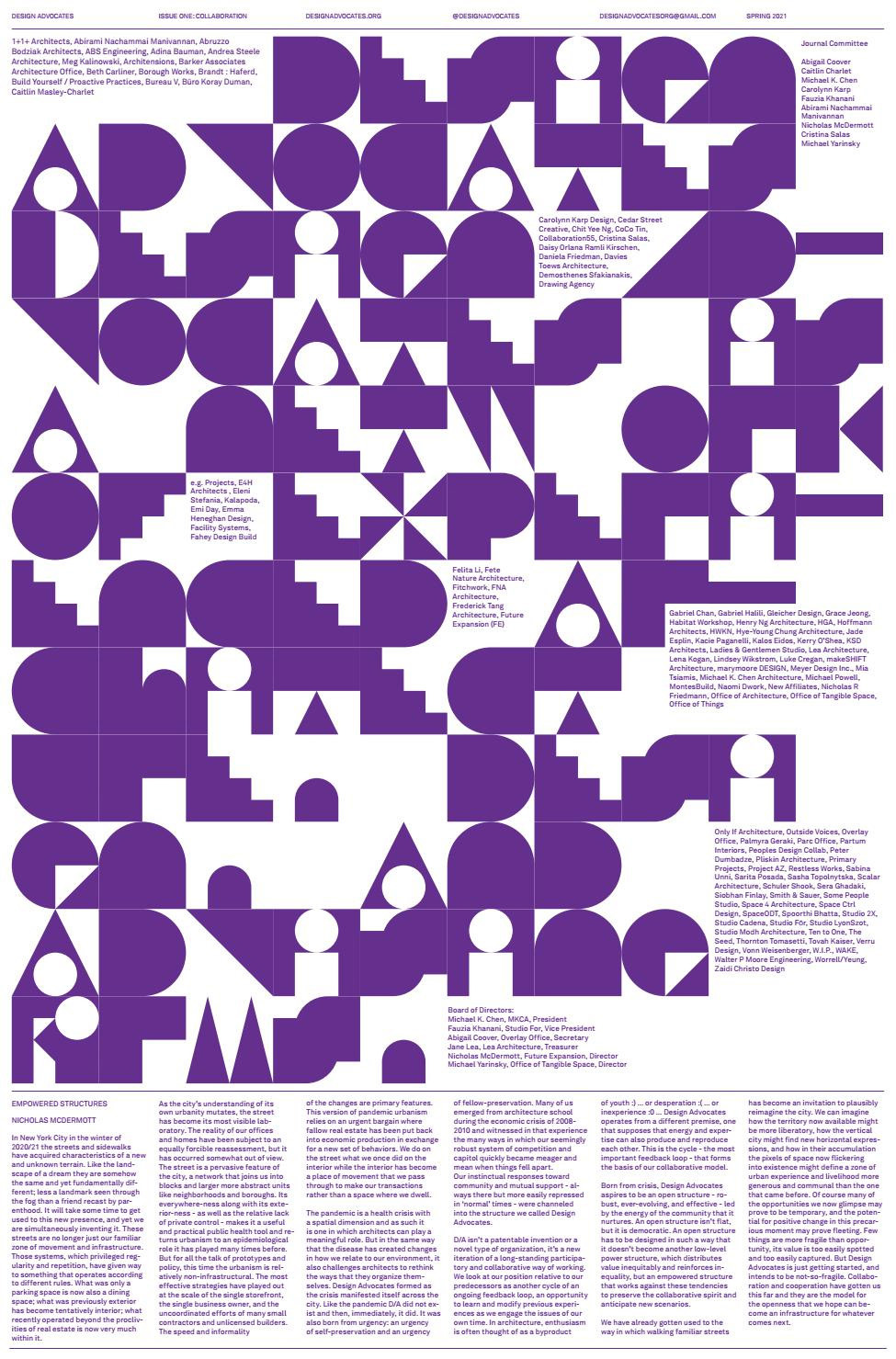

The pandemic is a health crisis with a spatial dimension and as such it is one in which architects can play a meaningful role. But in the same way that the disease has created changes in how we relate to our environment, it also challenges architects to rethink the ways that they organize themselves. Design Advocates formed as the crisis manifested itself across the city. Like the pandemic D/A did not exist and then, immediately, it did. It was also born from urgency: an urgency of self-preservation and an urgency of fellow-preservation. Many of us emerged from architecture school during the economic crisis of 2008-2010 and witnessed in that experience the many ways in which our seemingly robust system of competition and capitol quickly became meager and mean when things fell apart. Our instinctual responses toward community and mutual support – always there but more easily repressed in ‘normal’ times – were channeled into the structure we called Design Advocates.

D/A isn’t a patentable invention or a novel type of organization, it’s a new iteration of a long-standing participatory and collaborative way of working. We look at our position relative to our predecessors as another cycle of an ongoing feedback loop, an opportunity to learn and modify previous experiences as we engage the issues of our own time. In architecture, enthusiasm is often thought of as a byproduct of youth :) … or desperation :( … or inexperience :0 … Design Advocates operates from a different premise, one that supposes that energy and expertise can also produce and reproduce each other. This is the cycle – the most important feedback loop – that forms the basis of our collaborative model.

Born from crisis, Design Advocates aspires to be an open structure – robust, ever-evolving, and effective – led by the energy of the community that it nurtures. An open structure isn’t flat, but it is democratic. An open structure has to be designed in such a way that it doesn’t become another low-level power structure, which distributes value inequitably and reinforces inequality, but an empowered structure that works against these tendencies to preserve the collaborative spirit and anticipate new scenarios.

We have already gotten used to the way in which walking familiar streets has become an invitation to plausibly reimagine the city. We can imagine how the territory now available might be more liberatory, how the vertical city might find new horizontal expressions, and how in their accumulation the pixels of space now flickering into existence might define a zone of urban experience and livelihood more generous and communal than the one that came before. Of course many of the opportunities we now glimpse may prove to be temporary, and the potential for positive change in this precarious moment may prove fleeting. Few things are more fragile than opportunity, its value is too easily spotted and too easily captured. But Design Advocates is just getting started, and intends to be not-so-fragile. Collaboration and cooperation have gotten us this far and they are the model for the openness that we hope can become an infrastructure for whatever comes next.

As the city’s understanding of its own urbanity mutates, the street has become its most visible laboratory. The reality of our offices and homes have been subject to an equally forcible reassessment, but it has occurred somewhat out of view. The street is a pervasive feature of the city, a network that joins us into blocks and larger more abstract units like neighborhoods and boroughs. Its everywhere-ness along with its exterior-ness – as well as the relative lack of private control – makes it a useful and practical public health tool and returns urbanism to an epidemiological role it has played many times before. But for all the talk of prototypes and policy, this time the urbanism is relatively non-infrastructural. The most effective strategies have played out at the scale of the single storefront, the single business owner, and the uncoordinated efforts of many small contractors and unlicensed builders. The speed and informality of the changes are primary features. This version of pandemic urbanism relies on an urgent bargain where fallow real estate has been put back into economic production in exchange for a new set of behaviors. We do on the street what we once did on the interior while the interior has become a place of movement that we pass through to make our transactions rather than a space where we dwell.

The pandemic is a health crisis with a spatial dimension and as such it is one in which architects can play a meaningful role. But in the same way that the disease has created changes in how we relate to our environment, it also challenges architects to rethink the ways that they organize themselves. Design Advocates formed as the crisis manifested itself across the city. Like the pandemic D/A did not exist and then, immediately, it did. It was also born from urgency: an urgency of self-preservation and an urgency of fellow-preservation. Many of us emerged from architecture school during the economic crisis of 2008-2010 and witnessed in that experience the many ways in which our seemingly robust system of competition and capitol quickly became meager and mean when things fell apart. Our instinctual responses toward community and mutual support – always there but more easily repressed in ‘normal’ times – were channeled into the structure we called Design Advocates.

D/A isn’t a patentable invention or a novel type of organization, it’s a new iteration of a long-standing participatory and collaborative way of working. We look at our position relative to our predecessors as another cycle of an ongoing feedback loop, an opportunity to learn and modify previous experiences as we engage the issues of our own time. In architecture, enthusiasm is often thought of as a byproduct of youth :) … or desperation :( … or inexperience :0 … Design Advocates operates from a different premise, one that supposes that energy and expertise can also produce and reproduce each other. This is the cycle – the most important feedback loop – that forms the basis of our collaborative model.

Born from crisis, Design Advocates aspires to be an open structure – robust, ever-evolving, and effective – led by the energy of the community that it nurtures. An open structure isn’t flat, but it is democratic. An open structure has to be designed in such a way that it doesn’t become another low-level power structure, which distributes value inequitably and reinforces inequality, but an empowered structure that works against these tendencies to preserve the collaborative spirit and anticipate new scenarios.

We have already gotten used to the way in which walking familiar streets has become an invitation to plausibly reimagine the city. We can imagine how the territory now available might be more liberatory, how the vertical city might find new horizontal expressions, and how in their accumulation the pixels of space now flickering into existence might define a zone of urban experience and livelihood more generous and communal than the one that came before. Of course many of the opportunities we now glimpse may prove to be temporary, and the potential for positive change in this precarious moment may prove fleeting. Few things are more fragile than opportunity, its value is too easily spotted and too easily captured. But Design Advocates is just getting started, and intends to be not-so-fragile. Collaboration and cooperation have gotten us this far and they are the model for the openness that we hope can become an infrastructure for whatever comes next.

***

Written January 2021.

More information on Design Advocates is available here.