Anti-Symbolic Space

Washington should unsettle us more. The city foregrounds the symbolic power of architecture for historical purposes as much as any other urban center. Its height limits and wide boulevards create a horizontal city in which verticality and spatial position at the end of the grand cutting avenues are planning tools that permanently highlight privileged buildings and all of the metaphorical baggage that comes with them. And yet we live in a country of individuality and pop celebrity, with functioning myths of reinvention and mobility streamed in from reality TV and social networks. This is a country still obsessed with a two-century-old act of rebellion, so why don’t we spark at the friction of Washington’s rigid architectural hierarchy and relentless historicism?

In Washington, a building’s physical attributes like height, bulk, spatial isolation and iconic form are symbols for civic virtue. These same attributes make them excellent platforms for viewing all of the other buildings representing the same civic virtues. For example, the Mall’s long, flat sprawl is punctuated by the Washington Monument, a memorial and observation tower with aerial views of the city that expose a web of other symbolic structures. It is a redundant urban scheme, with everything emphasizing the same qualities in everything else and no contrast. The Mall has the potential to be that contrast, the messy forward-facing antithesis to Washington’s stonework and gravitas. It could be the beating heart of the stiffly metaphorical city, an anti-symbolic space absorbed by the present and shaped by activity, impulse, and meaningless daily activity. The ironic coexistence of ‘upward mobility’ with rising income inequality and of ‘personal responsibility’ with ‘too big to fail’, which produce the unique schizophrenia of our American experience, could then be channeled into constructive potential.

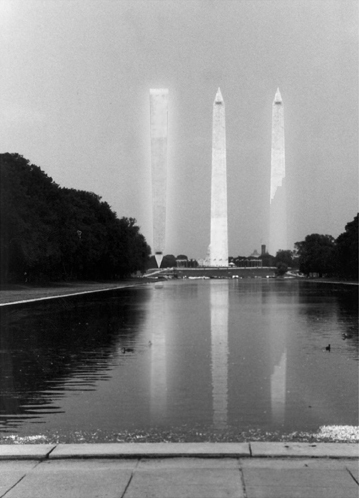

What would an anti-symbolic space look like? The Mall’s amorphous shape west and south of the Washington Monument already suggests a physical informality opposed to the overshadowing and didactic enclosure of the museums along the eastern periphery. Likewise, the dominating presence of General Washington’s Monument needs a dose of Founding Father-style plurality to play up the disagreement and personality that makes the country’s establishing story so compelling. We should obscure, multiply, and otherwise suggest new physical relationships between the Mall, the obelisk, and the symbolic city beyond. Instead of a place where protest and tourism are temporary pursuits, the Mall could be a pocket of active architectural openness inside the structured symbolism of the city—the structure supporting the openness and, ultimately, the openness legitimizing all that structure.